Recently growth mindset has become a major buzzword in education. When I began hearing the term, I started reading about growth mindset and quickly realized that the idea of growth mindset was something most great educators already believed long before the term was coined. However, there was now data and research to prove and justify that belief. As educators, we now have a great deal of information on ways to promote a growth mindset in our classrooms. While most of us will agree and support the idea of a growth mindset, we have to ask ourselves if our assessment and grading practices reflect that mindset.

I want to begin by saying that I completely understand that we are all bound to our district’s assessment policy guidelines, and I don’t encourage anyone to step outside their district’s and school’s grading guidelines. Fortunately, regardless of what our district’s or school’s grading policy, we can typically adapt our classroom grading to reflect a growth mindset to meet any guideline or requirement. I’ve used a growth mindset approach to grading with both traditional percent grading policies and standards based grading policies.

It’s important to reflect on our grading policy, because a growth mindset has to be embedded in practice to make the idea more than empty words for students and parents. Our assessment and grading may be one of the most important factors in facilitating a growth mindset for students, and if our grading policies do not reflect our own beliefs, then we are miscommunicating growth mindset to our students. This post shares 5 ways I’ve adapted my grading and assessments to foster an environment that encourages a growth mindset.

Only Grade Summative Assessments

The vast bulk of our assessments should be formative assessments. These formative assessments inform both teachers and students about student understanding at a point when adjustments can be made in time for summative assessments. These adjustments help to ensure students achieve learning goals within a set time frame. It is extremely important that we do not grade learning tasks and practice. While it is perfectly fine, even beneficial, to record formative assessments for data and classroom records, we should not record formative assessments as formal grades in our grade books. When students are in the learning process, they must feel safe and free to take learning risks, which is extremely difficult when students are facing the pressure of earning a passing grade.

We must also teach our students that failure is part of the learning process, and to begin shifting students’ emphasis away from grades to the actual learning. We should emphasize the importance of making mistakes and learning from failure, as this is when true learning occurs. You can read more about the importance of productive struggle here, and you can learn more about how I keep track of formative assessments here.

When we only grade summative assessments, we may notice a significant decrease in the number of grades we record each grading period, and this is okay. An abundance of grades is not necessary for excellent teaching or for student growth. When I made the shift of only grading summative assessments, I was a bit worried that students would not take their learning assignments seriously, but that wasn’t the case at all. My students began to shift away from the external motivation of a grade to the internal motivation of learning. Of course this wasn’t an overnight change, because this shift in mindset is a process.

Differentiate Assessments

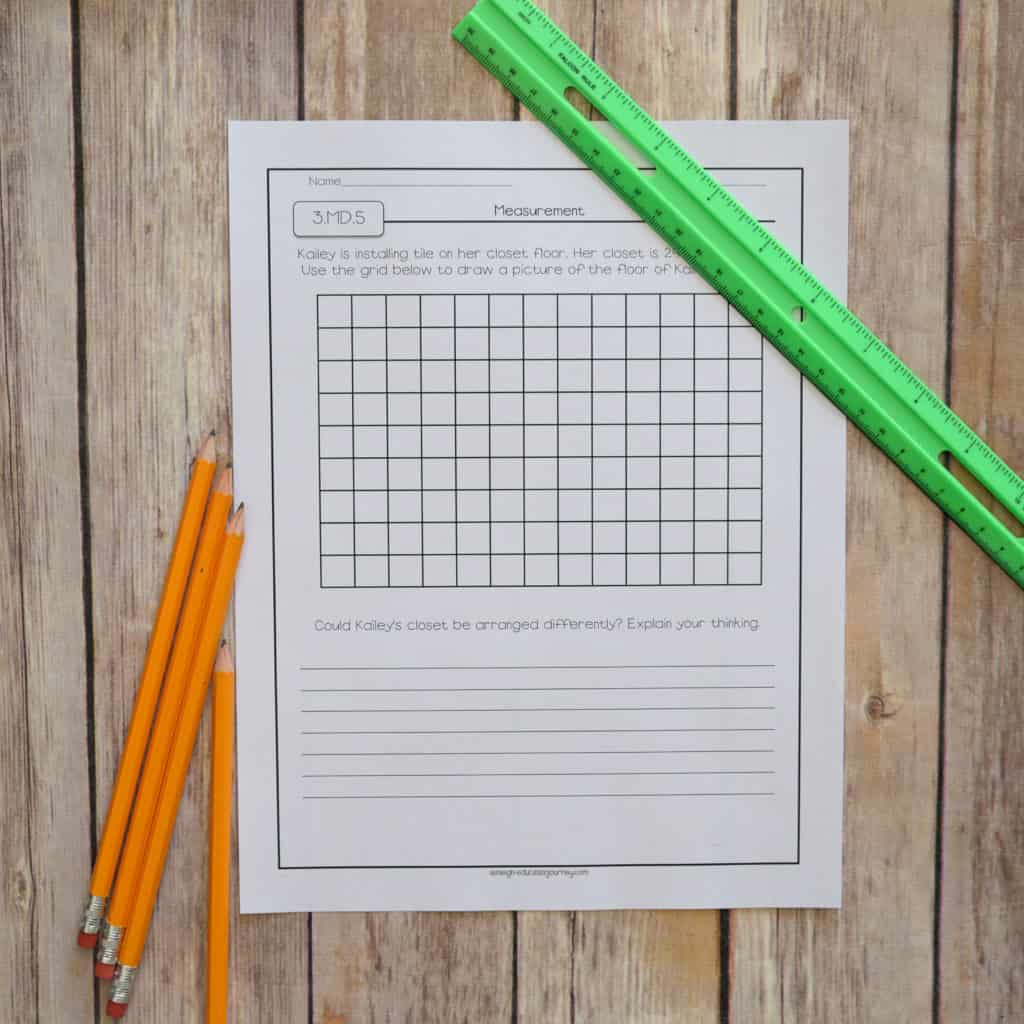

Not all students test well, so we have to make sure that assessments are differentiated so that all students who understand will be able to demonstrate their understanding. Make sure that assessments have a varied forms of questions that assess a variety of levels of comprehension, from basic recall to analysis and synthesis. It is also important to use alternative assessment techniques such as performance tasks, portfolios, and presentations. I certainly recognize that the state test my students take at the end of the year won’t be differentiated, so I always try to use a balanced form of summative assessments. I typically give one summative performance task, project, or presentation and one traditional pencil paper test.

Students Learn at Different Rates

When teaching with a fixed mindset, the curriculum sets a schedule or pace that must be followed whether students master the content or not. However, with a growth mindset, mastery can be shown at anytime within a reasonable timeframe. Of course most of us have curriculum maps to follow, but just because we’ve technically finished a unit doesn’t mean that we can no longer meet with students in small groups to reteach and reassess as necessary. I know that I’ve had several students who just weren’t ready for mastery of a concept when I gave our end of unit assessment, but after a few weeks of consistent practice, the light bulb came on.

There are many different philosophies when it comes to when and how to grade. Personally, I assess my whole class at the end of each unit. However, if I have a student who later demonstrates mastery on a standard I will change their grade to reflect that mastery. I want to make sure their grade reflects their understanding of the standard, not the rate in which the student mastered the standard. It’s not necessary to offer blanket reassessment policies, because I’m well aware of how that policy could be misused with some students. I’m talking about the students who are honestly giving their best effort, and it just took them a little longer to learn the content.

It’s important to remember that just because the lesson or unit over, doesn’t mean the development of the knowledge skills has be, too.

Grades Should Reflect Student Achievement

When we take points off for late work or add points for extra credit, it takes away from the grade assigned for achievement on an assessment. Our final report card grades should accurately reflect what the student knows and can do. When we assign summative grades, our grades must be relative to the standards and the student’s mastery of that standard. Even though it may be tempting, using fixed measures to coerce compliance does not help promote a growth mindset. When we grade completion of homework, mark off points for late work or misbehavior, we are grading work habits, rather than the mastery of a standard. With this practice, it is possible for someone totally proficient in math to fail math because of behaviors, not mastery.

There is also a possibility that a student can be deficient in an academic skill but receive passing grades because of good behavior and compliance. Behaviors and work habits are absolutely import and should be reflected as part of a student’s work habits grade. Of course when adopting this type of grading, there will always be issues arise where there isn’t a clear answer. What do I do about students who refuse to complete an assignment? Should students who make years worth of growth still fail if they haven’t met their grade level standards?

When these problems arise, and I like to discuss these with my administration and colleagues and handle them on a case by case basis. For these challenging situations, blanket statements and policies rarely work.

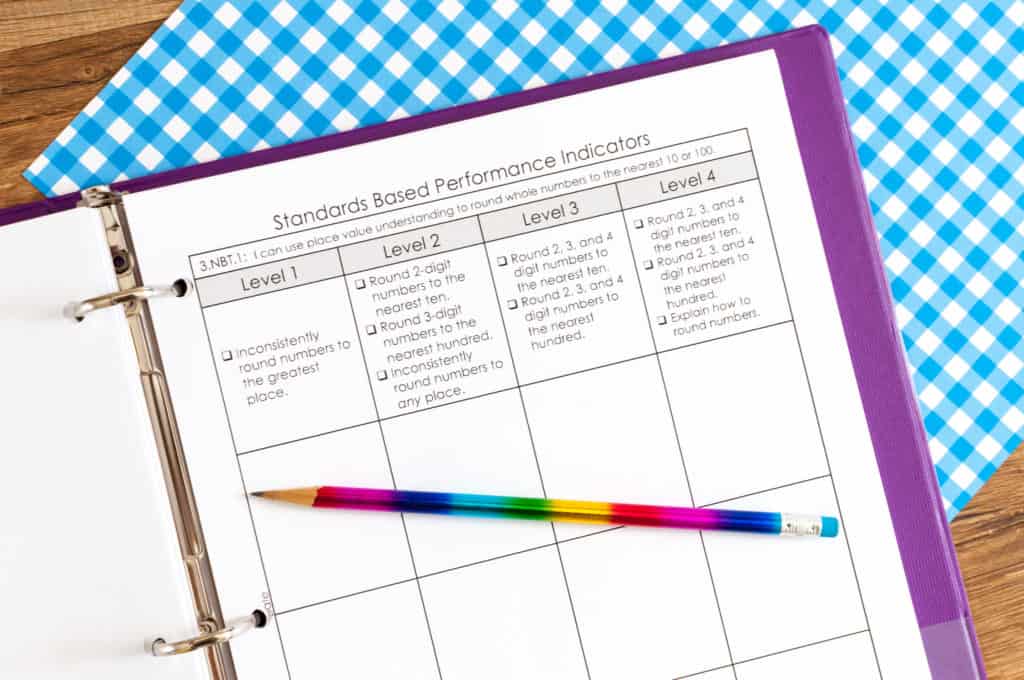

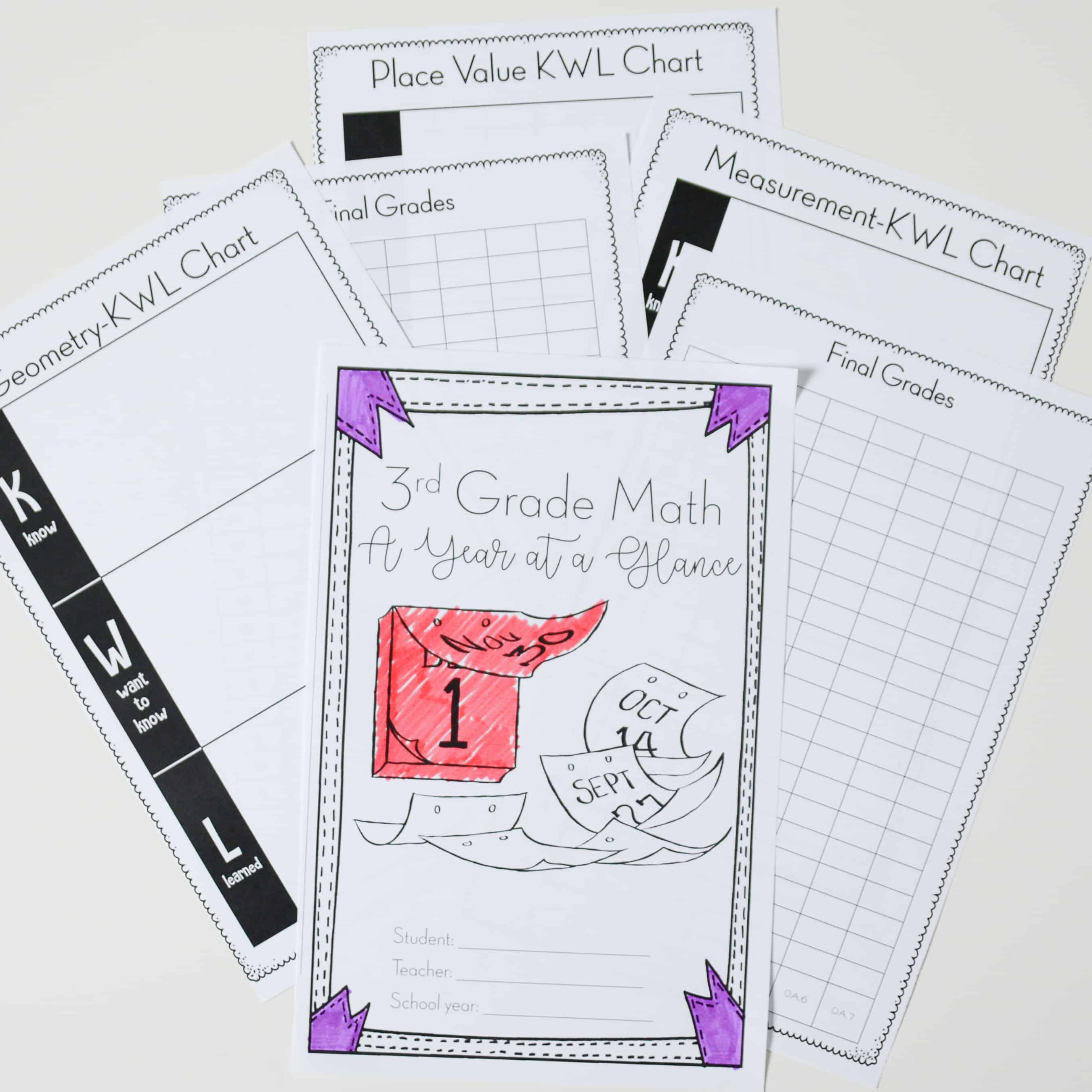

I also like to have students monitor their growth. It is encouraging for students to track their learning over time, because they are able to tangibly see the fruits of their effort. My students create a Year at a Glance Portfolio. In the portfolio, I have my students complete a KWL chart for each new math unit. Students complete the K and the W the day we begin the unit and the L as we work through the unit. Students also graph their scores for each standard. If a student reassesses and gets a higher score, they add to the bar graph with a different color. In the portfolio, I also have students keep a graph of the multiplication facts they’ve mastered and division facts they’ve mastered.

Feedback is Essential for Student Achievement

Effective feedback gives students information they use to increase their learning and improve their performance. We should focus feedback on student progress, strategy, persistence, effort, as well as accuracy and precision. Be sure to use specific comments like, “Great improvement on capitalizing the first letter in a sentence,” and avoid making comments that imply the student’s performance is based on natural ability, such as “you’re such a talented writer”. The feedback should be about the quality of the work, not the quality of the student. Avoid phrases such as “You’re so smart!” because that praises inherent ability which encourages a fixed mindset.

To promote a growth mindset through feedback, it is important to provide praise around effort and how the problem was solved, rather than the innate ability to solve problems. That doesn’t mean that we can point our areas of weakness, and only focus on effort. Our feedback should offer students specific support on how to grow or improve academically.

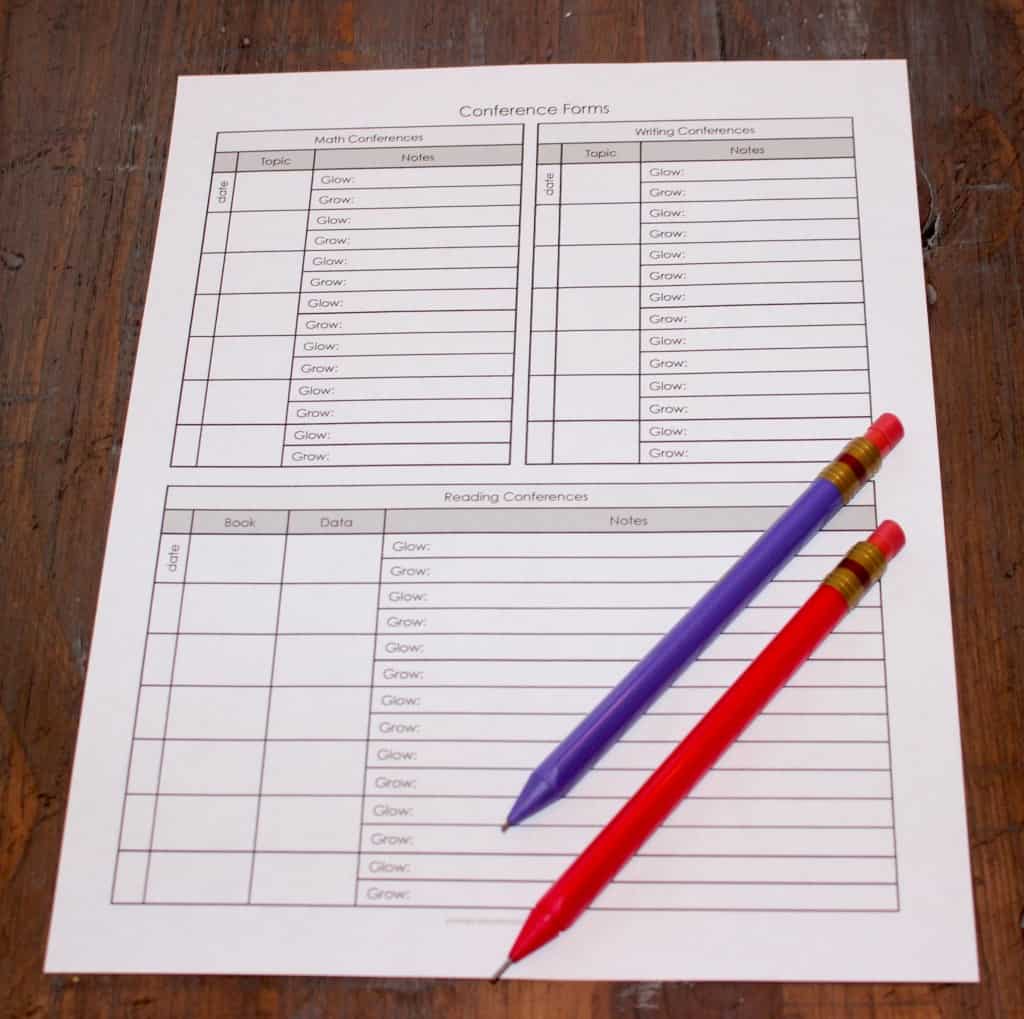

I like to keep a record of student conferences where I give students feedback. When we meet, I always start with a “glow” what specific piece of the content showed mastery of the standard, or where do I see considerable growth. We then discuss a “grow” which is the student’s next step. Keeping a record of your feedback is another great form of formative assessment.

Hi Ashleigh,

I have a question concerning growth mindset and grading. For the academically gifted student in a classroom of students with less capability/skill, is it appropriate to assign that student a grade reflecting one’s own goals for that particular student? For instance: the gifted student easily can make an A on the material assessment. . . I decide the student needs more challenge, so I set a different subjective standard for this student and give the student a B to attempt to nudge him or her towards growth mindset. (I am not providing more challenging material, just harder for them to earn that A than before in my own mind.) Is this appropriate? Furthermore, is it okay to do this without the student’s or the student’s parents’/guardians’ consent? At one point does this cross the bounds from “growth mindset” to actual academic gaslighting?

That is a great question!! I think it would depend on your district’s policy. In mine, we would not be allowed to do that. However, we could add comments to the report card, but for each standard, we’d report what the student earned on that grade level standard.