We’ve all taught the student who appear to refuse to make any effort at all in the classroom or the student who constantly gives the shoulder shrug and the dreaded, “I don’t know”. This can all be attributed to learned helplessness, which is the belief that behavior does not control outcomes or results. A student with learned helplessness thinks, “No matter how hard I study or work, I’ll always get a bad grade,” and then no longer appear to make any effort. Students who experience repeated school failure are the most likely to develop a learned helplessness. These students begin to doubt their own abilities and begin to decrease their efforts and develop a pattern of giving up when facing difficult tasks. Common characteristics of students with learned helplessness include: not paying attention, waiting for the teacher to help, refusing to start work without assistance, asking for constant affirmation, and verbally stating that they don’t know how to do something. Fortunately, there are things we can do in our classrooms to prevent learned helplessness. Because it’s learned helplessness, it can also be unlearned.

High Expectations

Setting high expectations may sound counter productive, but they’re essential for preventing learned helplessness. This is especially true for teachers at Title One schools or teachers who teach students with disabilities. I’ve taught 15 years in a high poverty, Title One school, so I am well aware of the many challenges students and teachers face. However, I’ve seen first hand the amazing growth and success our students can have when they know we believe in them and fight for them to receive the best education possible. We have to avoid caveats such as: I work in a Title One school, so my students aren’t motivated; I teach in a low income school, so parents aren’t involved; or I teach special needs students so they can’t…

We can’t lower our expectations, because of a child’s circumstances. Students can, and will, rise to our expectations.

We can’t fall into the trap of saying, “Johnny has a bad home life…” and allow Johnny to cut corners and take the easy way out, because we feel sorry for him. Nor can we excuse a lack of work ethic or behavior issues because of unfortunate circumstances. Instead, I want to teach Johnny the absolute best I can to give the tools he needs to rise above his circumstances.

Having high expectations is about more than students learning challenging material and doing quality work. It can also mean that instead of giving failing grades for poor quality work, you make the student redo the assignment until it meets the quality that you expect. When we have high expectations, we do not have to be rigid or inflexible. However, the standards that we set should be those necessary to achieve the goals we want for our students, and flexibility should be allowed when there are many ways to achieve those goals. We do need to be able to provide some compromises for students with circumstances outside their control. For example, I would not penalize a student for not being able to have a parent or adult sign a reading log or agenda. However, I would offer an alternative such as having the student sign as a promise that they did the assignment. We never want to set our students up to fail.

Our beliefs about our students create a self-fulfilling prophecy. The self-fulfilling prophecy begins with the expectations we have about our students. We communicate those expectations to students though body language, assignments, our language, and how much time we spend with individual students. Students typically react to the way that we communicate those expectations to them. Students should believe that there is no limit to their potential and ability to learn.

Allow Struggle

It is often our natural tendency to immediately step-in and intervene as soon as a student faces any type of difficulty. Unfortunately, this does more of a disservice to the student than our help provides. We all have students who need constant affirmation “is this right” or students who have a hard time getting started on almost any task “I don’t know what to do”. Our students are conditioned to ask for help the minute something doesn’t go right or they are stumped. Students have to learn how to answer their own questions. If we want to develop life long learners, we must teach students how to figure it solutions to their problems for themselves, even if it involves some struggle. I’ve written a blog post decided to productive struggle that you can read here.

For this to be effective it is essential to have the right class environment. Students must feel safe to take risks. Students have to be taught that it’s okay to try and to fail. They must shift their mindset to thinking that failure can be a learning tool, not an end result. Students must also feel safe and comfortable to share with their classmates. They need to know that their ideas and suggestions won’t be laughed at or belittled. It’s also necessary to take away the fear of making a bad grade. A learning task is not a task that should be graded for the purpose of recording a grade in the grade book.

Many students have learned that if they wait to begin their work, teachers will give them more and more help — to the point where, if they wait long enough, the teacher will help them through every step of completing a task. We have to stop giving answers or excessive support. When we help too much, we communicate we don’t believe students can do it independently. Of course some students will require more support than others, but no matter how much support a student needs I don’t want to eliminate the struggle completely, as it is a necessary part of the learning process. Sometimes I have to force myself to physically walk away, because I know as long as I maintain close proximity, the student will be waiting on my assistance.

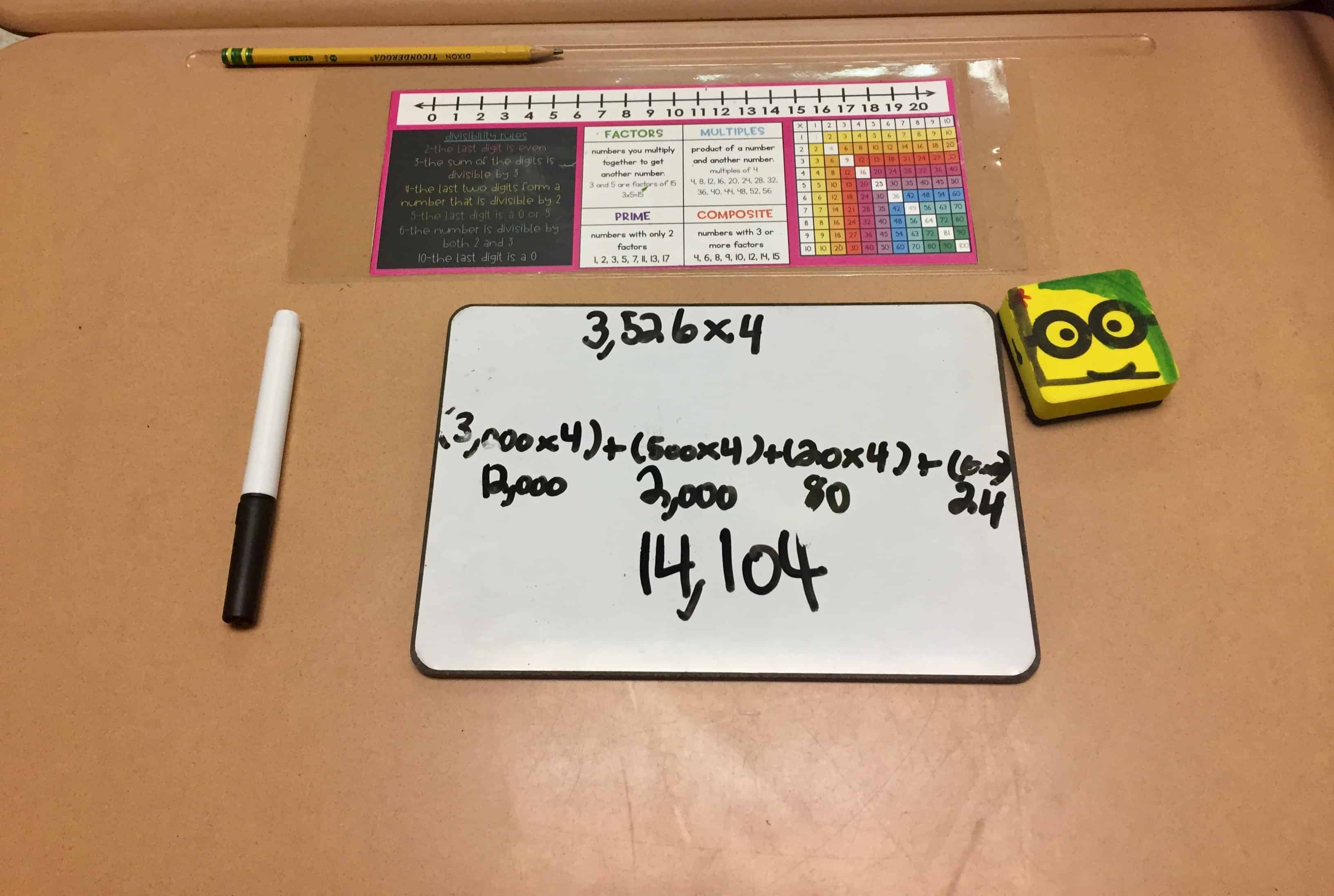

One great strategy is to increase your wait time. Wait time is the period of silence between the time a question is asked and the time when one or more students respond to that question. It is necessary to give students some time to think about the questions and formulate a response. The amount of time you wait after asking a question will depend on the complexity of your question. I also implement a form of wait time when we begin a math task. My students call it “struggle time,” as I don’t help students get started. Instead, I require them to strategize and problem solve. When that time is over, before I provide guidance, I have students show many what strategies they used. Unsuccessful strategies and attempts can give me great insight into my students mathematical reasoning.

Provide Resources

We’ve established that we must maintain high expectations and not immediately rescue students from struggle, but we have to make sure we are not setting up our students to fail. We must create opportunities for students to experience success. What is considered a success for one student may completely different for another student, which is why it is so important for us to differentiate for students. When students’ assignments are interesting, challenging and varied, they require different abilities. Since different learners have different abilities, students can take turns as leaders with these varied roles.With this in mind, I try to always build in scaffolding and/or differentiation to allow my students to feel successful.

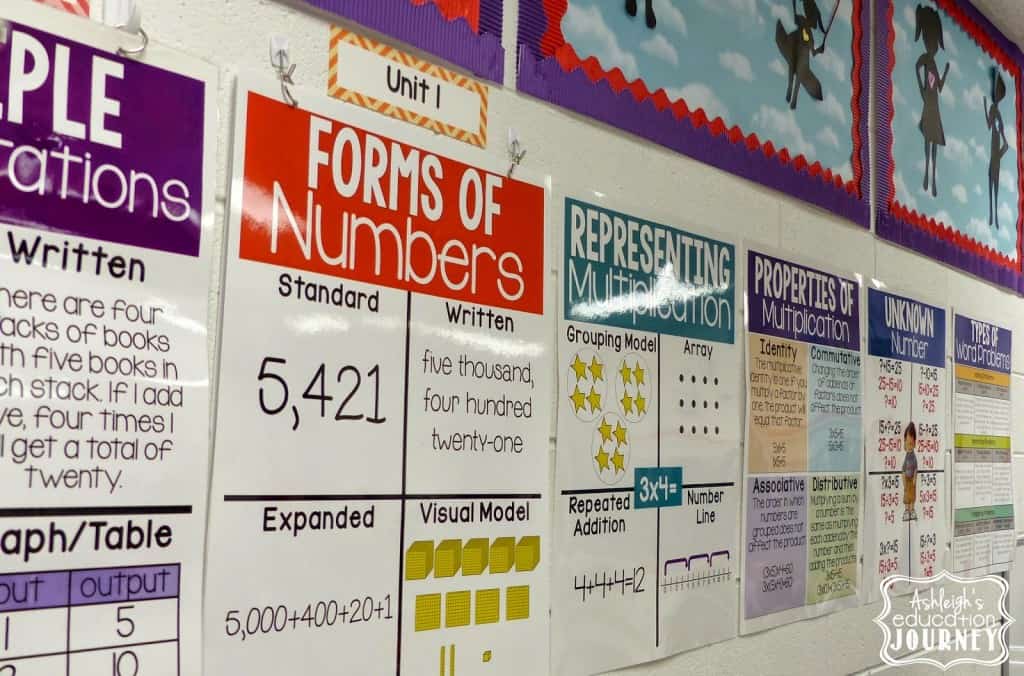

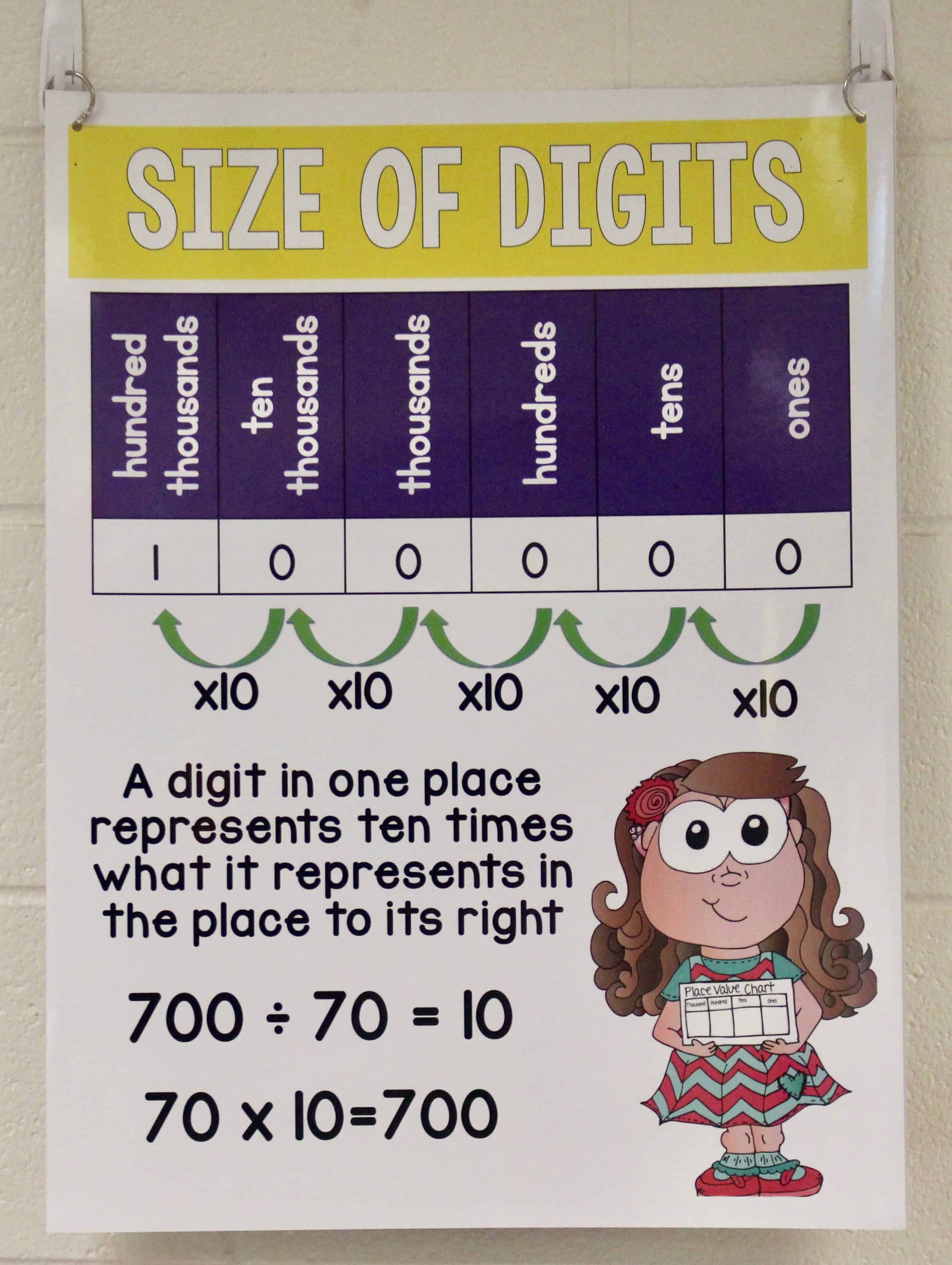

I am careful to provide resources to foster independence, which is not the same as spoon feeding. I hang anchor charts in my classroom that students can refer to as needed. In my classroom, I have them for math, reading, social studies, and science. You can find my anchor charts here.

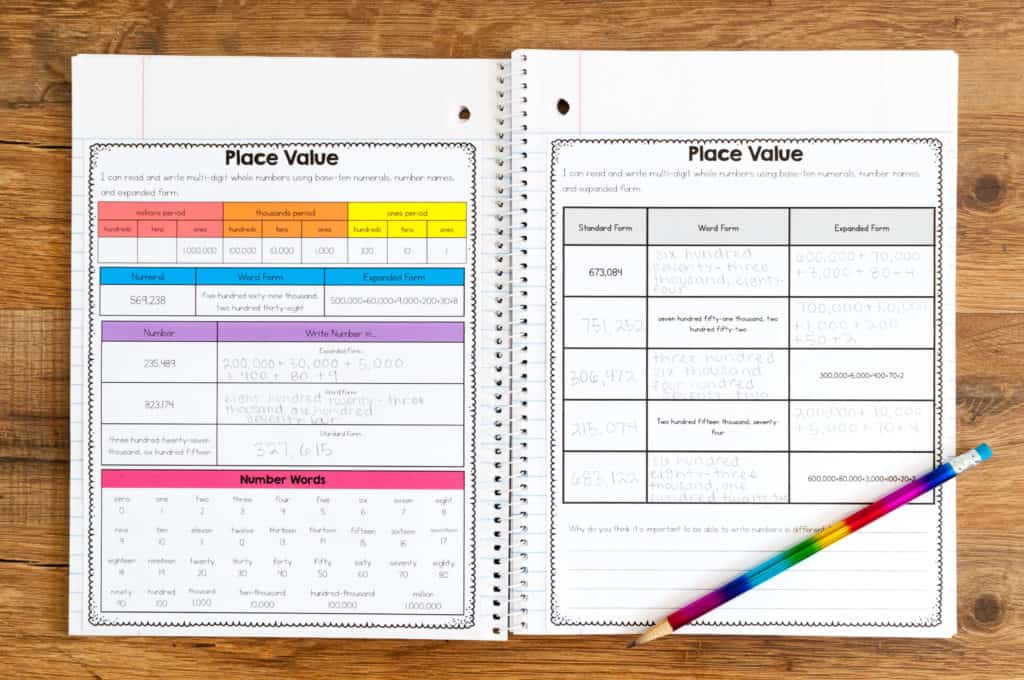

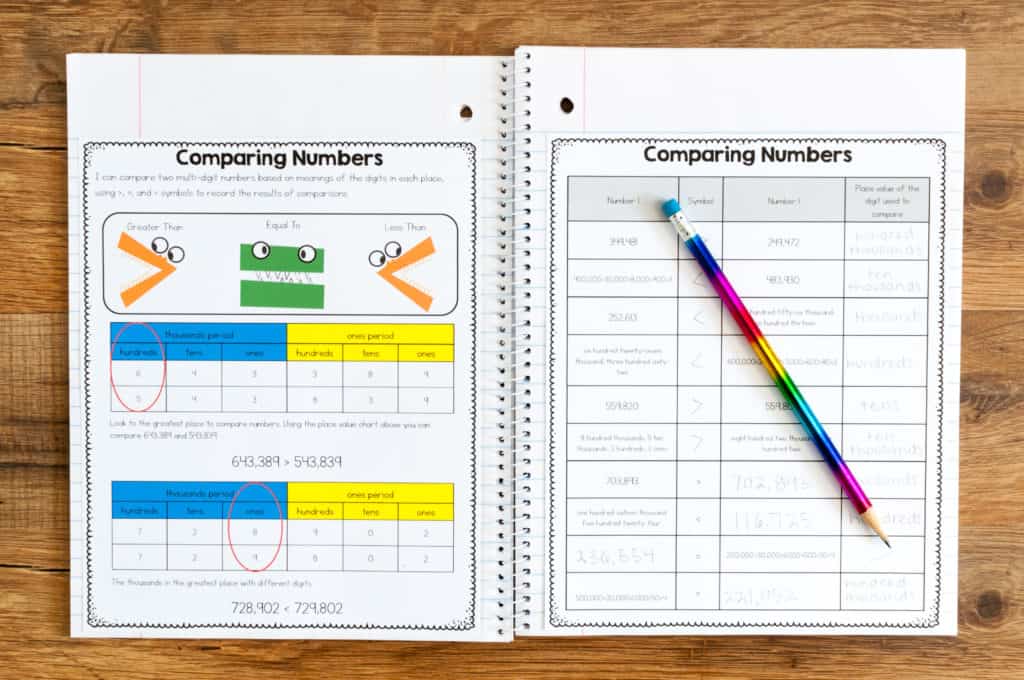

My FAVORITE resource for math are my math reference notes, which I have for third and fourth grade math. You can find those here. Last year students cut the pages out and placed them inside their math notebooks. This year I had the reference notes printed and bound to eliminate all cutting and pasting. My students reference these notes all. of. the. time. It’s really neat to see how as students internalize concepts, they no longer need the notes. I don’t require students to use their notes, but they take the initiative, which I love!

Another resource that has been particularly useful are my desktop helpers, which I have four third and fourth grade math, which you can find here. I plan to make a language arts version of this and the reference notes soon! I’ve included a little video so you can see how I use the desktop helpers. I bought the pouches on Amazon, so far I haven’t had any peel or tear.

Hopefully, some of these strategies will help you and your students. I’m always looking for new suggestions and ideas, so feel free to leave them in the comments!

Thank you for all the wonderful ideas and resources. What do you do with the student who struggles staying on task while doing independent work – the child who zones out or is extremely slow, but very capable of completing the given work?

Wonderful article!